The American Shakespeare Center has been ‘doing it with the lights on’ at the Blackfriars Playhouse in Staunton, Virginia since 2001. For ten years, this small theatre on Market Street has brought the staging conditions of Shakespeare productions and his contemporaries to life in a beautiful re-creation of Shakespeare’s Blackfriars Playhouse (the world’s only re-creation, in fact). As many of the preshow speeches dictate, the use of universal lighting creates a unique environment for audiences and actors in which “they can see you, you can see them and you can all see each other.” This essentially avant-garde brand of theatre is attributed to the loyalty the American Shakespeare Center has on early modern practices. The playhouses in Shakespeare’s period would have been lit by either sunlight or candlelight, neither of which could have been dimmed or altered for the purpose of the production. This knowledge allows the American Shakespeare Center to support academically their choice to keep the lights at the same level throughout each and every production. Living, studying, and working in this community has altered my conception of theatre forever. I was an English major whose only exposure to live Shakespeare performances was at Public Theatre’s Shakespeare in the Park in New York City. After eight months here now, I can’t really imagine seeing Shakespeare in the dark ever again. To be honest, I don’t know if I would enjoy theatre as much if the actors couldn’t see, talk to, and engage with me as an audience member. Theatre here is a continual conversation with the audience, and I cannot really imagine being shut out of that conversation ever again (although I still would like to see the Broadway Addams Family.)

To clarify my seeming divergence, the reason I have brought up our universal lighting practices and the American Shakespeare Center preshow is that universal lighting seemed to me as a characteristic of early modern theatre that common practice had abandoned until the American Shakespeare Center and places like it brought the conversation back into the light and the audience back into the play. Can we really believe that after proscenium arches and footlights the audiences was always in the dark? Can we as theatre audiences accept that the conversation just stopped until 2001 in Staunton, Virginia? Or rather, in 1988 when Dr. Ralph Alan Cohen and Jim Warren founded Shenandoah Shakespeare Express (the theatre company that would eventually become the American Shakespeare Center)? I am sure lights-on productions happened throughout those few hundred years of interim. This assurance turned into a hypothesis, and I started reading about the historical evolution of theatre and theatre audiences. I picked up a book of that same title, Theatre Audiences by Susan Bennett, and found one section that was of particular interest to me. In the section entitled “Historical Approaches to Theatre” she breaks down the evolution of theatre in terms of audience throughout history:

“A history of audiences in the theatre demonstrates, of course, a changing status. Medieval and sixteenth century audiences did not enjoy the power of the Greek audiences, but nevertheless still functioned in an active role. There was flexibility in the relationship between the stage and audience worlds which afforded, in different ways, the participation of those audiences as actors in the drama. With the establishment of private theatres in the seventeenth century, however, there is a move towards separation of fictional stage world and audience, and with the beginnings of passivity and more elitist audience came codes and conventions of behavior. In terms of English theater, audiences became increasingly passive and increasingly bourgeois. With the exception of the first forty years of the nineteenth century-when the working-class audience created noisy disturbances and occasional riots in the pits- this is a steady progression to a peak in the second half of the nineteenth century. After 1850, with the pits replaced by stalls, theatre design ensured the more sedate behavior of audiences, and the footlights first installed in the seventeenth century private playhouses had become a literal barrier, which separated the audience and the stage. As Michael Booth puts it, ‘After 1850 behavior improved, and complaints were eventually made, not of uproar in the pit and gallery, but of stolid indifference in the stalls.’ In the last hundred years, none the less, there have been many challenges and disruptions of the codes and conventions which demand passivity.”

After reading this breakdown, I realized that the evolution of theatre over the past hundred years was designed to make everyone behave and follow the rules of social conduct. With the lights off, your options are limited. Your choices are either to pay attention to what’s in the light, to make out with your date, or to fall asleep. Limiting the choices of the audience removed the conversational element the Blackfriars has completely from the plays. Susan Bennett goes on to mention the consequence of proscenium theatre: passive audiences. I thought of theatre productions where passivity in the audience was actively combated against. In the Blackfriars Playhouse, actors talk directly to audience members. They present questioning lines as questions and wait for responses. The actors even physically interact with audience members. This practice destroys the comfort zone that would traditionally foster a passive audience. I can recall numerous productions where this frees audience members, and pulls them further into the world of the play. I can also recall multiple instances where audience members are unsure of how to act. The American Shakespeare Center breaks three hundred years of theatre behavior rules, and they expect their audiences to forget the rules they were raised in and to see an early modern play without concerns for the code of etiquette. Audience members are invited to sit on stage, to answer the actors, and to look wherever they please. They can even get up and get a drink at the bar whenever they would like to. The American Shakespeare Center actors create the world of the play for the audience and then invite them to live in it fully instead of just observing a show.

As I continued reading Susan Bennett’s Theatre Audiences I came across the phenomenon in the twentieth century. Productions started dissolve the convention of the fourth wall and to shock audiences out of the stasis of passive observation. Throughout the fascinating list of avant-garde early twentieth century production style, I came across one that hit close to home. Susan Bennett explains the theatre style of Meyerhold’s production of Lermentov’s Masquerade, a production in Russia in 1917 that kept the lights on in the theatre throughout the production. I shared this exciting bit of information with my boyfriend, a former theatre professor and current Masters Student from New York who perked up at the mention of Meyerhold. I will fully admit I did not know who this man was. I was simply excited that people other than the American Shakespeare Center and early modern England had “done it with the lights on.” I proceeded to Google, as any good scholar would. I found that Meyerhold had worked in Russia and eventually took over for Constantin Stanislavski as director his theatre. For those of you who did not go to acting school, as I did not, Stanislavski is a big name in the acting world. He essentially invented the method of acting that directly opposed the Western method acting movement of the time:

Meyerhold's acting technique had fundamental principles at odds with the American method actor's conception. Where method acting melded the character with the actor's own personal memories to create the character’s internal motivation, Meyerhold connected psychological and physiological processes and focused on learning gestures and movements as a way of expressing emotion outwardly. Following Stanislavski's lead, he argued that the emotional state of an actor was inextricably linked to his physical state (and vice versa), and that one could call up emotions in performance by practicing and assuming poses, gestures, and movements. He developed a number of body expressions that his actors would use to portray specific emotions and characters. (Although Stanislavski inspired method acting, he was also at odds with it, because like Meyerhold, his approach was psychophysical).

From my reading and various discussions with actors I have gleaned that Stanislavski was instrumental in the evolution of acting as it exists today. Meyerhold was essentially his legacy in the world of Russian theatre and is now the link between their revolutionary production style and American Shakespeare Center’s choices to “do it with the lights on.” According to The Russian Theatre Under the Revolution by Oliver M. Sayler written in 1920, Meyerhold made many of the same choices in production as the American Shakespeare Center makes now. “In performance, it was sheer joy,--the joy of the theatre as theatre. You face Meyerhold's stage with no illusion that it is not a stage. Of course it is a stage! Why pretend it isn't? There it is, under the full lights of the auditorium, curtain removed and apron extended twenty feet beyond the proscenium arch. It's a play you shall see, a play, you who love the theatre for its own sake! No cross-section of life here, no attempt to copy life! No illusion here, to be shattered by the slightest mishap or by a prosaic streak in the spectator's make-up. It's a play you shall see, and you'll know it all the time, for you'll play, too, whether you realize it or not. The audience is always an essential factor in the production of drama.”

I was excited to make this discovery and to share it with all of you. I hope you find it as interesting as I did. I think that it is always nice to realize your world is far larger and more influenced than you originally thought. While the American Shakespeare Center is not the first modern theatre to keep the lights on the audience and to invite everyone into the world of the play, the ASC is in good company.

(K.A. Lenz)

negotiate with the French King Charles IV, who agreed to name Henry his successor and seal the deal with a marriage to the French princess Catharine. Charles was in poor health and had suffered some time from mental illness, so it seemed that Henry would outlive him and soon seize the crown with his French queen at his side. Unfortunately, a bout of dysentery killed Henry two months prior to the death of the French King. Henry never wore the crown of France, and he left an infant behind as King of England. England’s dominance of the French was short-lived, and Shakespeare chronicles the loss of Henry’s gains in the Henry VI trilogy.

negotiate with the French King Charles IV, who agreed to name Henry his successor and seal the deal with a marriage to the French princess Catharine. Charles was in poor health and had suffered some time from mental illness, so it seemed that Henry would outlive him and soon seize the crown with his French queen at his side. Unfortunately, a bout of dysentery killed Henry two months prior to the death of the French King. Henry never wore the crown of France, and he left an infant behind as King of England. England’s dominance of the French was short-lived, and Shakespeare chronicles the loss of Henry’s gains in the Henry VI trilogy.

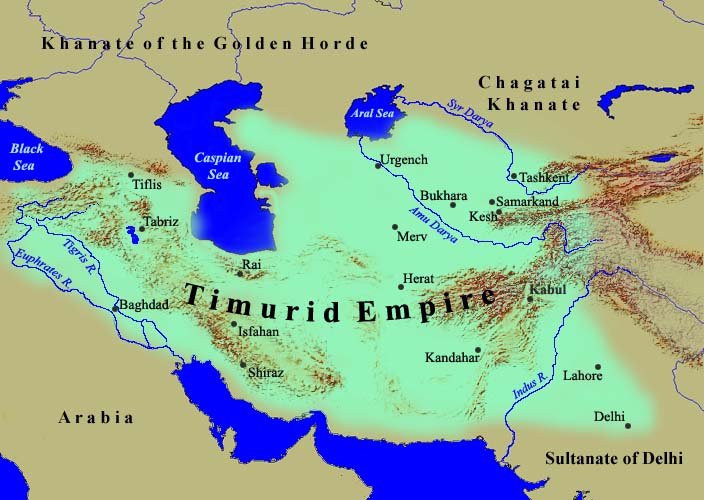

y this character’s history couldn’t be as extraordinary as that of the great English king. Well, that’s true; it’s actually much more extraordinary. Marlowe’s play is loosely based on the life of Timur, a one-of-a-kind, hardcore Mongolian warrior. His name “Timur” comes from a word meaning “iron”. If that conjures up images from Rocky IV, then you’re getting the right picture. An exhumation of his remains confirms that he was broad-chested and tall with strong cheek bones. The Persians dubbed him Tamburlaine, which essentially translates as “Timur the lame” (he reportedly limped from a battle injury. The injury, however, doesn’t seem to have deterred his fierceness).

y this character’s history couldn’t be as extraordinary as that of the great English king. Well, that’s true; it’s actually much more extraordinary. Marlowe’s play is loosely based on the life of Timur, a one-of-a-kind, hardcore Mongolian warrior. His name “Timur” comes from a word meaning “iron”. If that conjures up images from Rocky IV, then you’re getting the right picture. An exhumation of his remains confirms that he was broad-chested and tall with strong cheek bones. The Persians dubbed him Tamburlaine, which essentially translates as “Timur the lame” (he reportedly limped from a battle injury. The injury, however, doesn’t seem to have deterred his fierceness).

ple their own army. He, like Henry, ordered the execution of prisoners on several occasions. If prisoners showed the slightest sign of revolt, he wouldn’t hesitate to execute tens of thousands at a time.

ple their own army. He, like Henry, ordered the execution of prisoners on several occasions. If prisoners showed the slightest sign of revolt, he wouldn’t hesitate to execute tens of thousands at a time.

.jpg)

Proud Mamas - Elizabethan sisters and their babies (ca. 1599).

Proud Mamas - Elizabethan sisters and their babies (ca. 1599).

“Perchance he’s hurt i’ th’ battle.” All’s Well that Ends Well, 3.5.86

“Perchance he’s hurt i’ th’ battle.” All’s Well that Ends Well, 3.5.86